Cardiovascular disease management is an often overlooked but critical aspect of care for people with type 1 diabetes, authors of a new review paper said.

Cardiovascular disease is the most common cause of death in type 1 diabetes, as it is in type 2 diabetes. Yet, there are no randomized clinical trial data to support cardiovascular risk interventions for people with type 1 diabetes specifically. Professional society recommendations for lipid-lowering are developed primarily from trials of people with type 2 diabetes and are conflicting, said the authors of the review, published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Cardiovascular risk management typically receives far less attention than glucose management in type 1 diabetes office visits, especially in younger adults, review lead author Camila Manrique-Acevedo, MD, professor of medicine in the Division of Endocrinology at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, told Medscape Medical News.

"Type 1 diabetes in a certain way is where type 2 diabetes was 20 years ago, in the sense that we used to be extremely glucose-centric, but we were kind of forgetting about cardiovascular risk. That has totally changed in the type 2 diabetes world. Now with type 1 diabetes we're realizing that while glucose control is extremely important, it is not enough. Things like strict blood pressure control and lipid control are lagging behind in type 1 diabetes," she said.

One reason is the lack of clinical trial evidence for lipid, blood pressure, antithrombotic, and obesity interventions in type 1 diabetes. And "I also think that because people with type 1 diabetes are often younger, it doesn't always click that they are at extremely high cardiovascular risk," Manrique-Acevedo said.

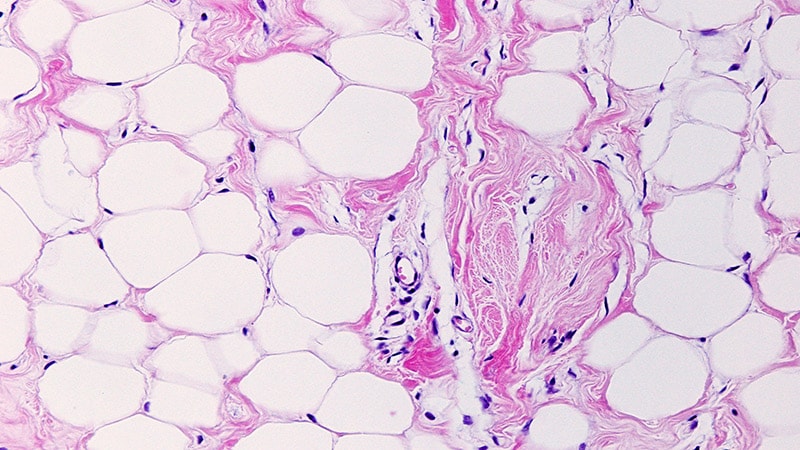

Moreover, achieving tight glycemic control in type 1 diabetes can lead to weight gain, which adversely affects cardiovascular health. "If you gain more weight, you are going to be at higher risk of hypertension and other complications from excess weight gain. When we see patients with type 1 diabetes, we want the A1c to be [at target], but we aren't always addressing excess weight gain because it's not easy to address. And there is a risk of hypoglycemia. There are many things that come into question that we don't yet have all the tools to address," she said.

Asked to comment, Viral Shah, MD, professor of medicine and director of diabetes clinical research at the Center for Diabetes and Metabolic Diseases, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, told Medscape Medical News, "over many years, we have been focused on the A1c and microvascular complications in type 1 diabetes and were not even thinking about macrovascular. Now it's time to think about it. So I would highly encourage people to start thinking about cardiovascular and neurocognitive issues, particularly in middle-aged to older groups that have not been talked about in the past."

Biology: Similar to Type 2 But Also Different

Manrique-Acevedo's coauthors on the review paper were Irl B. Hirsch, MD, professor and diabetes treatment and teaching chair at the University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, and Robert H. Eckel, MD, professor of medicine emeritus, Division of Endocrinology, Metabolism and Diabetes, Anschutz Medical Campus, University of Colorado, Denver.

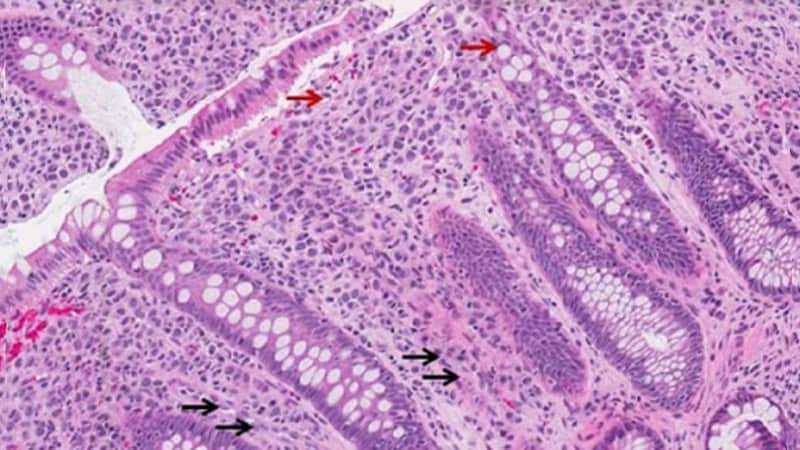

They begin with a review of the biology of cardiovascular disease in type 1 diabetes. Many of the mechanisms are believed to be similar to those in type 2 diabetes, but there are some differences. For example, obstructive coronary heart disease appears to be less extensive in type 1 than in type 2, but vascular wall inflammation appears higher, independent of glycemic control.

And, as was shown in the 6.5-year follow-up to the landmark DCCT, tight glycemic control clearly reduced cardiovascular event risk in participants with type 1 diabetes. In contrast, data have conflicted regarding the relationship between glycemic control and cardiovascular risk in type 2 diabetes.

Kidney disease is also closely aligned with cardiovascular disease in type 1 diabetes, the authors wrote.

Statins: Conflicting Recommendations, Especially in Younger People

In a box, the review paper summarized recommendations for statin use in type 1 diabetes from the American Diabetes Association (ADA), the American College of Cardiology (ACC)-American Heart Association (AHA), the European Society of Cardiology, and the International Society of Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes (ISPAD).

Both the ADA and ACC-AHA recommend at least moderate-intensity statins for people with type 1 diabetes aged 40-75 years, with differing criteria for when to consider high-intensity statin therapy. The ADA and ISPAD give differing guidance for youth older than 10 years. None of the recommendations specifically address the 18- to 39-year age group.

Manrique-Acevedo and coauthors advised cardiovascular risk assessment in all patients with type 1 diabetes, including consideration of obtaining a coronary artery calcium (CAC) score. Data have suggested that a CAC score of 100 or higher predicts cardiovascular risk.

In a supplement, they provided a clinical vignette of a 34-year-old man with type 1 diabetes diagnosed at age 10 years with no history of cardiovascular disease or symptoms and no albuminuria. His total cholesterol level was 210 mg/dL, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol was 125 mg/dL, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol was 45 mg/dL, triglyceride was 200 mg/dL, and A1c was 7.0%.

Based on ADA's guidance, his diabetes duration and LDL cholesterol would merit "an opportunity to review the recommendations and with shared decision-making consider statin therapy. Alternatively, the clinician can also consider measuring a CAC score and/or a lipoprotein(a) before deciding what to do."

Shah said that for adults with type 1 diabetes younger than 40 years, he routinely recommends statins for those who've had type 1 diabetes for more than 20 years. For those with shorter duration or who prefer not to take a statin, he recommends a CAC assessment and statins for those with scores above 100. For others, it's an individualized decision.

He pointed to data from his own study of 8727 adults with type 1 diabetes from the T1D Exchange Clinic Registry, showing that the 5-year incidence of cardiovascular disease was 3.7%. Higher risks were seen with older age, longer diabetes duration, overweight/obesity, higher A1c, hypertension, dyslipidemia (based on triglyceride/HDL ratio), and nephropathy.

In that study as in others previously, LDL cholesterol levels did not differ between those who did and did not develop cardiovascular disease. "Some have postulated that the LDL-C particle size and its oxidation is different in people with T1D, which also depends on glycemic control. Therefore, CVD risk is higher in people with T1D even at near-normal LDL levels. Studies have suggested a reduction in CVD risk with statin therapy irrespective of baseline LDL-C levels," Shah and colleagues wrote in their discussion.

Also Important: Glycemia, Blood Pressure, Antithrombosis, Obesity

The review included a second box summarizing more agreed-upon recommendations for: 1) A1c < 7% if possible without increased hypoglycemia, 2) blood pressure control to < 130/80 mmHg or better, < 120/80 mmHg with treatment including renin-angiotensin-aldosterone blockade, and 3) aspirin 75-162 mg as either primary prevention in patients aged > 50 years with additional risk factors or secondary prevention in those with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

For obesity management, recommendations include caloric restriction and increased physical activity aimed at achieving 5%-10% weight reduction, consideration of referral to a lifestyle modification program, and consideration of a glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist with shared decision-making regarding potential side effects. Bariatric surgery has also been shown effective and safe in people with type 1 diabetes and obesity, they noted.

Commenting on recent data showing that type 1 diabetes occurs in about 1 in 200 people in the United States, Manrique-Acevedo said, "It's not a rare disease. It's happening more and more in young adults."

Manrique-Acevedo and Eckel had no disclosures. Hirsch reported grants from Dexcom, Tandem, and MannKind and personal fees from Abbott Diabetes Care, Roche, and Vertex. Shah reported grants from Novo Nordisk, Alexion, and Insulet; payment or honoria for presentations from Dexcom, Tandem Diabetes Care, and Embecta; and participation on a Data Safety Monitoring Board for Dexcom, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, and Medscape Medical News.

Miriam E. Tucker is a freelance journalist based in the Washington, DC, area. She is a regular contributor to Medscape Medical News, with other work appearing in the Washington Post, NPR's Shots blog, and Diatribe. She is on X: @MiriamETucker.

.webp) 1 week ago

9

1 week ago

9

English (US)

English (US)