This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Laura is a 34-year-old nurse who consults you in clinic because she's waking frequently through the night with aching and jumpy legs. She often has to get out of bed to walk and stretch her legs to relieve her symptoms. As a result of this ongoing sleep disturbance, Laura feels tired all the time and is struggling to fulfill her work commitments. Laura probably has a restless legs syndrome (RLS). What do we need to know about RLS in primary care?

RLS, also known as Willis-Ekbom disease, is common in primary care. For some people, it's a simple annoyance; for others, symptoms are more severe and affect their quality of life and sleep. It is these individuals whom we often see in clinic.

The prevalence of RLS is estimated at 5%-10% of European and North American adults; of these individuals, 2%-3% experience moderate to severe symptoms that have a significant impact on their quality of life. Women are affected twice as often as men, and the average age of diagnosis is the fourth decade — just like our case patient, Laura. A positive family history is also very common, found in over 50% of cases.

RLS is characterized by an overwhelming urge to move the legs, with associated discomfort. These symptoms are partially or totally relieved by movement. It usually occurs in the evening or at night and can be accompanied by abnormal sensations such as burning or tingling; occasionally, individuals may describe the sensation of insects crawling under their skin.

Importantly, some people will not present with these classic symptoms and may present only with sleep disturbance or restlessness at night. Be sure to ask patients about symptoms of RLS during any sleep-related consultations.

The pathophysiology of RLS has not been fully elucidated, but it is related to iron and dopaminergic pathways in the brain. Differential diagnoses to consider include nocturnal leg cramps, which involve sudden, involuntary, and painful muscle contractions in the legs and are usually unilateral. We also need to exclude peripheral neuropathy, which has multiple etiologies including diabetes, excessive alcohol intake, certain medications, and vitamin B12 deficiency.

Hypnic jerks can also mimic RLS. These are sudden jerking movements that occur as you are about to drop off to sleep. Peripheral vascular disease needs to be excluded, though as we all know, intermittent claudication is usually related to exercise and is not generally worse in the evenings or at night.

Finally, it is important to exclude akathisia. The word akathisia is derived from the Greek for "inability to sit." It is a feeling of inner restlessness and an inability to sit, stand, or lie still for a reasonable period of time. It is often associated with the use of antipsychotic medication, and symptoms bear no relation to the time of day.

RLS is predominantly primary or idiopathic but can also be secondary to certain conditions. The three most common secondary causes of RLS are iron deficiency, pregnancy, and end-stage kidney disease.

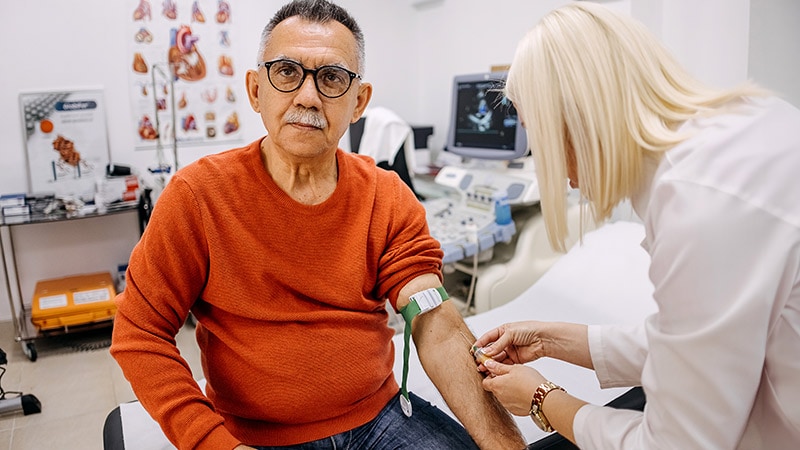

Around 1 in 4 people with RLS have iron deficiency, but not all people with iron deficiency have RLS. Current recommendations suggest investigating for a cause of iron deficiency if the serum ferritin level is < 50-75 µg/L. We should prescribe iron supplements as appropriate.

If we are prescribing iron for iron deficiency anemia, one tablet daily of an oral iron preparation is sufficient. If this is not tolerated, reduce the dose to one tablet on alternate days or consider an alternative preparation. Remember, ferrous fumarate contains more elemental iron (65 mg per tablet) than does ferrous sulfate (60 mg), so it's unlikely to be better tolerated.

In addition, RLS affects up to 1 in 4 pregnancies and tends to worsen as pregnancy progresses, but then settles spontaneously after delivery. RLS also affects around 1 in 5 people with end-stage kidney disease on dialysis, and there is a relationship between RLS symptoms and length of time on dialysis.

Finally, RLS can be secondary to certain neurologic conditions, including parkinsonism and multiple sclerosis, and certain medications, including antidepressants, such as the SSRIs and SNRIs, prochlorperazine, and antihistamines. Secondary RLS can also be associated with vitamin B12 and folate deficiency, as well as excess caffeine, alcohol, and chocolate intake.

How do we manage RLS in primary care? We need to identify and correct secondary causes of RLS where possible, as I've just discussed. We should assess severity of symptoms using our clinical judgment or a validated score, such as the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group Rating Scale, which can be found online.

For people with mild symptoms, we should reinforce lifestyle advice and simple strategies to manage symptoms during an attack. Lifestyle advice includes good sleep hygiene; reducing caffeine and alcohol consumption; stopping smoking; and undertaking regular, moderate-intensity exercise.

Simple strategies to relieve an episode of RLS include walking, stretching and massage of the affected limbs, use of heat with heat pads or a hot bath, or relaxation exercises. For those with moderate to severe symptoms that significantly affect quality of life, we should also reinforce lifestyle advice and simple strategies to relieve symptoms, but we should also consider medication.

First-line pharmacologic options for people with frequent or disabling symptoms of RLS are either a dopamine agonist, such as pramipexole, ropinirole, or rotigotine, or a gabapentinoid, either pregabalin or gabapentin. Note that these latter two options are off-label indications. We should no longer offer opioids for the treatment of RLS.

There's been a real shift away from the use of dopamine agonists over the years due to augmentation of symptoms, loss of efficacy, and the risk of impulse control disorders. Augmentation is where symptoms of RLS are worsened with longer-term use of dopamine agonists. Symptoms can occur earlier in the day, are increased in intensity, and can spread to the arms or trunk.

Augmentation can develop months or even years after treatment is started. It affects around 7% of people on dopamine agonists for RLS. Augmentation is associated with higher doses of dopamine agonists, so we should use the lowest dose to improve quality of life, but this may not necessarily eradicate symptoms.

We can also consider as-required dosing of dopamine agonists or long-acting dopamine agonists, such as rotigotine patches, to reduce the risk for augmentation. Long-acting dopamine agonists are also useful for those with significant daytime symptoms owing to their long duration of action. Also, we can consider regular trials of dose reduction or frequent drug holidays to minimize the risk for augmentation.

Loss of efficacy is also commonly seen in long-term treatment of RLS. Over time, the drug dose often needs to be increased to maintain the original effect on symptoms.

Finally, treatment with dopamine agonists has a well-established association with impulse control disorders, including pathological gambling, binge eating, and hypersexuality. Impulse control disorders occur in around 1 in 5 people with RLS who take dopamine agonists and are common in women, those on higher doses, and in those with a history of illicit drug use or a family history of gambling disorders. We need to warn individuals about the risk for an impulse control disorder and actively inquire about symptoms at each review consultation.

However, we are stuck between a rock and a hard place, because gabapentinoids are also not without their significant adverse effects, including dizziness, sedation, increased appetite and weight gain, as well as suicidal thoughts and behavior. Furthermore, pregabalin and gabapentin are controlled drugs in the United Kingdom, with potential for misuse, abuse, and harm.

First-line choice of medication for RLS should be individualized according to symptoms, comorbidities, and potential side effects. A dopamine agonist is preferable for more severe symptoms in people who are living with obesity or overweight, who have comorbid depression or cognitive impairment, or who are at an increased risk for falls. A gabapentinoid is preferred first-line therapy for those with significant sleep disturbance, comorbid anxiety or pain, or a history of an impulse control disorder.

For Laura, history and examination were strongly suggestive of RLS. Blood tests revealed a ferritin level > 75 µg/L. However, symptoms were having a significant impact on her quality of life and work.

I reinforced lifestyle advice and discussed simple strategies for symptom management. However, given her occupation as a nurse, she was perturbed by the possible symptoms of dizziness, sedation, and weight gain with the gabapentinoids. So we opted for a dopamine agonist, lowest-dose pramipexole, to be taken 2-3 hours before bedtime as required in the first instance to minimize the risk for augmentation.

To finish, a quality improvement activity for us all in primary care: How many of our patients with RLS have had their ferritin levels checked?

.webp) 1 week ago

6

1 week ago

6

English (US)

English (US)