This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Matthew F. Watto, MD: Welcome to The Curbsiders. I'm Dr Matthew Frank Watto, here with America's primary care physician, Dr Paul Nelson Williams. I'm excited to recap the discussion we had with Dr Michelle Kittleson on our cardiac amyloidosis podcast, and share our favorite pearls.

Amyloidosis is super-rare, right? If I'm seeing or admitting a patient with HFpEF, I don't need to consider amyloidosis on the differential?

Paul N. Williams, MD: I love that we're back to this teaching style. The main takeaway from our podcast was that amyloidosis is probably far more prevalent than we thought. Every article says it's a rare diagnosis. But Dr Kittleson told us that in one case series, 1 in 8 patients who went through aortic valve replacement for aortic stenosis had evidence of amyloidosis. It's probably considered rare because we haven't always diagnosed it.

Watto: Dr Kittleson has a pet peeve that's helpful. When an echo report says left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy, how do we know it's hypertrophy? We would need to do a biopsy to confirm that the muscle fibers are hypertrophied. Instead, we should say increased wall thickness because we don't know whether the tissues are thickened from hypertrophy or from an ongoing infiltrative process, such as amyloidosis.

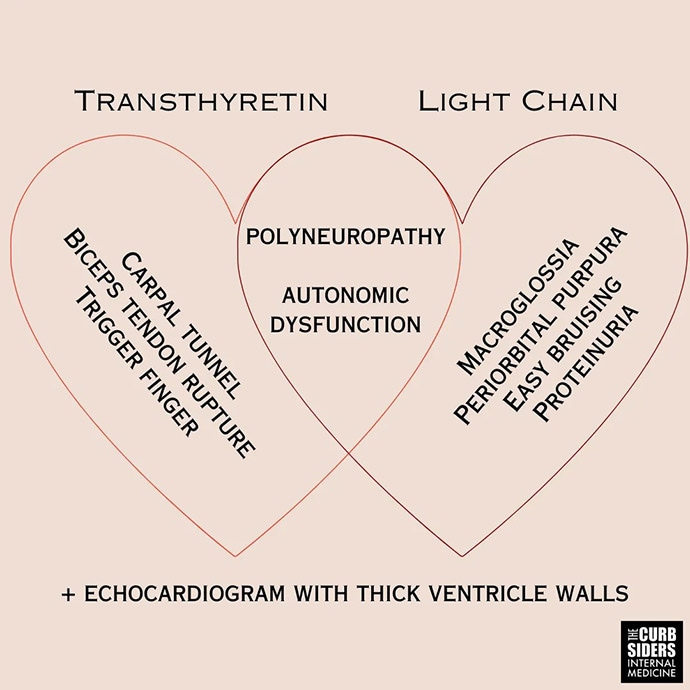

That's one of her rules: Say "LV thickness increase" rather than "LV hypertrophy." We created a figure to help us remember the features of the two main types of cardiac amyloidosis: light chain (AL) and transthyretin amyloidosis (ATTR). What are the clinical features that we should look out for?

Williams: ATTR occurs more often among older patients. New bilateral carpal tunnel syndrome at age 60 is weird, especially without a reason to have it, and should raise the hackles on the back of your neck. The biceps tendon rupture — the classic Popeye arm — and even trigger finger, to some extent, should raise suspicion for ATTR in the right clinical context. For light chain, it's macroglossia; periorbital purpura; easy bruising; and frothy, foamy urine, which might indicate proteinuria.

Polyneuropathy and autonomic dysfunction overlap both amyloidosis types. But there is a difference in terms of urgency of referral and evaluation, depending on what you suspect and what you're looking for in the workup.

Watto: If the echo shows increased ventricular wall thickness and one of these other red flags, then you should consider amyloidosis. It's easier to diagnose than you might think once you look for it. You can check for light chains by getting a serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) and urine protein electrophoresis (UPEP) immunofixation electrophoresis and serum free light chains — all tests that most internists order from time to time if they are thinking about something like nephrotic syndrome.

If those tests are positive, you may have found a case of AL amyloidosis, which carries a poor prognosis. You need to get that patient hooked up with hematology right away for a bone marrow biopsy to confirm the diagnosis.

Williams: But if the serologies are negative and you don't suspect AL amyloidosis, the next thing you worry about is ATTR amyloidosis, which is diagnosed with technetium pyrophosphate (Tc-PYP) scintigraphy. If that is negative, you start looking for other causes.

If it's positive but light chains are negative, the patient meets criteria for ATTR and you might not even necessarily need a tissue biopsy. So the Tc-PYP is a neat test to fast-track a diagnosis.

Watto: That's the test to see whether the heart lights up more than the bones — a positive test. They have ATTR cardiac amyloidosis. And if they do have that, there's a drug called tafamidis, which is very expensive. It's a pill, and if patients can get it, it does have improved cardiovascular outcomes. It's basically a stabilizer of the TTR amyloid fibrils. So, that is the treatment algorithm. As internists, we're probably not going to be prescribing tafamidis, but we might be prescribing guideline-directed medical therapy for heart failure. Do we have to be careful with it? Should we be aggressive?

Williams: First, let me pat myself on the back. I joked about the major side effect of tafamidis being poverty. To your point, if you're chasing down this guideline-directed medical therapy that we're all fairly used to, you should know the unique features of these patients. They are very sensitive to volume shifts. Dr Kittleson told us that we should think about amyloidosis in a patient for whom you start a low-dose vasodilator (for example, when managing hypertension). These patients just do not tolerate it; they feel lightheaded and dizzy. You need to be cautious about vasodilation and diuresis because these patients are very sensitive to both. If you aren't careful, you can make them feel much worse.

Watto: If a patient with heart failure is having these wild responses to diuretics or vasodilator therapy, could it be amyloidosis? More than just your run-of-the-mill HFpEF or HFrEF. It's a lot to think about. Our guest, Dr Kittleson, was amazing. We couldn't touch on all the pearls on this short video, so click here to listen to the full podcast.

.webp) 2 days ago

3

2 days ago

3

English (US)

English (US)